Virginia Johnson Today - Before Carrie Bradshaw, Madonna, Sex and the City, Dr. Ruth, She Was Pioneer of Female Sexuality for American Women

The following excerpted from the new biography, "Masters of Sex: The Life and Times of William Masters and Virginia Johnson, The Couple Who Taught America How To Love," (Basic Books).

For those who knew her well, there was something disturbing about Virginia Johnson’s ignominious fate. How could one of the most remarkable American women of the 20th Century – who witnessed more about human sexuality than anyone in the world, who explored its multitude of physical wonders and emotional expressions -- be relegated to such obscurity? How could an independent-minded woman who embodied so many cultural changes in the world’s view about female sexuality be so unappreciated? Where were the 1970s feminists and the sexually confident young women of Generation X, those who emulated “Sex and the City” and text-messaged men asking for a date? These urbane, sophisticated women -- as much as any conservative suburban wife who might sneak a peek at Masters and Johnson’s books -- owed a debt to her more than they knew. As much as any woman in the last half century, Johnson advocated successfully on behalf of a women’s right to be treated equally as a man in the most intimate, often most personally satisfying, areas of life. Yet somehow, her own outcome made it seemed as if she’d suffered one more indignity in a man’s world.

Despite her many ailments, Virginia didn’t feel sorry for herself. The unsinkable spirit of a Missouri farm girl inside wouldn’t allow it. “This neuropathy is stupid,’ she said one afternoon slouched in a chair, her legs too weak to stand for very long. “Normally it leads to amputation and I’m not going to go that way.” Instead she dreamed of seeing her own memoir finished or perhaps a movie that might tell her story. When asked by a St. Louis gossip columnist if she planned to write an autobiography, she replied, “Yes, because I am afraid someone else will do it.” Years earlier, ABC television tried to make a film about the famous sex reseachers, reportedly with Shirley MacLaine portraying her, but the production collapsed because Gini wouldn’t cooperate with the scriptwriter’s demands. In recollections of her glorious past, she dropped enough names to hint at the breadth of her fame, sometimes with an air of unreality. She wanted Mike Nichols to produce the movie of her life and for Gore Vidal to write its screenplay. Maybe someone like Joanne Woodward could play her, and perhaps Robert Duvall as Bill Masters. The memories and reveries were still vivid enough to fill an empty afternoon. As a woman who once set the status quo aflame, she now enjoyed observing other assertive women like Madonna, those who never let the world define them. “Anyone who invents himself and who reinvents himself all the time, I always have a certain amount of admiration for the ability to do it,” she explained. “I love talent. I love people who can perceive and anticipate what people will buy. I think it's intriguing as the devil.”

If television producers didn’t call any more for bookings, if publishers didn’t offer large sums for her advice, it didn’t matter to her, Virginia claimed. “I don’t want any more credit,” she insisted. “I don’t give a damn. Every talk show immediately knows what my role was. The fact that I didn’t have an MD, half the people don’t even know it.”

The only thing about sex and love that still mattered to her remained the most unattainable, the most elusive part of her own life.

* * *

On a cold overcast day in October, Virginia stopped talking about her life for a moment, so she could rise from her livingroom chair, stretch her aching body and gaze out the window. From several floors above, she watched the people walking along the street near Washington University, where she and Bill once made medical history.

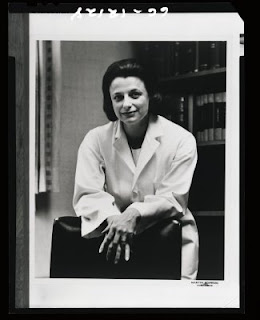

“I like being married -- I hate not being married now,” she admitted. “I was always a man’s woman. Always. Anyway you want to see it.” The room was filled with unopened boxes and storage crates. On the floor was a framed eight-by-ten publicity photograph of herself from a decade earlier, when men, she said, still found her desirous and attractive. “I’ve always pleased men. I always enjoyed adapting, to blend my interaction with them. I just enjoyed men.”

This pleasant apartment complex in St. Louis was her third residence in two years, each move to a place slightly less grand. The doorman and apartment manager were instructed to keep any visitors from her, even deny that she lived there if asked. The aura of secrecy from her work as a famous sex researcher still enveloped her existence. She had lived in so many different places, adopted so many name variations as her own. Forgotten were the names Gini and Mary Virginia. Even the name she’d been known as to the world, “Virginia E. Johnson”, was gone. In the telephone book, she was now listed as “Mary Masters” – still identified with the man who had been her partner, if not her love.

For a woman of such independence, who had proven in the lab the sexual equality if not the superiority of women, she found it inexplicable why her life had been defined so often by men. Was this her own fault, the result of society’s conditioning or simply the nature of things between men and women? She still wasn’t sure. “I was raised to be one of the greatest support systems to great men,” she explained, in a moment of revelation. “I can remember saying out loud -- and I’m appalled as I remember it -- being very pleased that I could be anything any man wanted me to be. And I was proud of that, for some ungodly reason.” She shook her head slowly, her thick eyeglasses balanced on her nose.

Twilight now turned the street scene below to shadows and shades of grey. Winter was coming to St. Louis and a chill could be felt against the pane. She turned from the window and stared at the old publicity photo of herself on the rug. “In retropect, I ask myself, ‘Geez, did I lose myself that totally?’ ” she wondered. “But I was very much a product of my time, of the era. In my mind, that was the ultimate as a woman. And I lost myself in there for quite a while.”